sometimes i forget

how to do the things

i say i like to do

Hart House Student Art Committee Winter Talking Walls Exhibition

Some day, you loved. And you begin to forget.

The Hart House Studnet Art Committee’s 2026 Winter Talking Walls student exhibition: “sometimes i forget how to do the things i say i like to do” explores what remains when passion comes to a halt; works that capture the fragility between memory and oblivion, wanting and doing.

This exhibition is a space for that dissonance, for the failure of unrequited love; not for completions, but for those who once professed love to art and now wait for an answer that never returns, for artists who open a sketchbook only to close it again, for drawers filled not with finished works but with projects frozen mid-gesture.

Your eyes may still be fascinated by the composition, light and vibracy of a scene–but your hands no longer dare to translate what your eyes see.

Do you say goodbye to past passions? Or do you still cry out for it to return? For some, this exhibition may be a farewell. For others, an act of resistance. It does not need to arrive at a conclusion, for that, too, is a path. To display what could never be finished does not mean to end it. Our aim is not to close, but the refusal of it. We are simply curious about how you continue to walk across all that you could not complete.

Eejin Choi and Mario Zhang

Hart House Art Committee

Student Projects Co-Chairs

Phynn Saunders

Gay & Can't Drive. 2025

Acrylic on masonite board.

I spent a year painting roads, I had never spent so long lingering on one subject-matter before. I would only paint when in the throws of great emotional turmoil, using the process of quick-drying paint as the vehicle for instant-gratification catharsis.

They started when my partner had moved back to Texas, I was overrun with fear. I found myself longing for a simple car-ride with them, an intimate act I took for granted, a 5-30 minute drive of pure trans joy and safety. This series brought me back to myself, and I am forever grateful.

Drive safe.

Monique Mattia,

Edmonton vs Utah, 2025.

Acrylic on canva-paper.

Utah Mammoth at Edmonton Oilers - Oct 28, 2025

Monique Mattia,

Happy Birthday, 2026.

Coloured pencil on black drawing paper. 9"x6".

Beatrice Moldoveanu

Summer, 2009. 2025.

Acrylic on unprimed canvas.

If something is so special to me, why can’t I recreate it on my own? A depiction of the neighbourhood sidewalk from my childhood in the summer of 2009, this piece explores the push and pull between memory and longing, when one is able to recall feeling but not place. The peaceful scene, now only visitable when framed by the artificiality of an internet search, reveals not only the impermanence of place, but of one's ability to remember it once it has disappeared.

Veronica Wong

I Don't Remember How to Paint (Items From My Childhood). 2026.

Oil paint on half inch canvas.

Maybe it’s because I’ve become busy with school and other things in recent years, but I don’t remember how to paint. This feeling is terrifying because, as far back as I can remember, making art has been the only thing I have ever been sure of how to do, and I am slowly forgetting. Of late, I’ve been pushing myself to paint more, even if it’s just things from around my room, things from my childhood, to relearn this skill that I hold so dearly.

Gurleen Manak

A to B. 2025.

Graphite on Poster Board.

I’ve realized I do not pay too much attention to the world around me. I move from point A to B without stopping to take in my surroundings or watch what others are doing. Whether it is a stained street, a mess of pipes running along the ceiling, or textures of clothing, developing these contour drawing has helped me become more patient, and also more aware of the spaces I pass through in my day-to-day life. This process of drawing has allowed me to discover and recognize what I tend to ignore.

Malachi Wilson

Skewed Tree Study, 2025.

Gel medium transfer on wood.

The tree in this image was pulled from a vintage magazine, and distorted through both digital and mechanical processes. I often want to retreat to nature, but find my relationship with it constantly mediated by other things that I project onto nature as a concept. I want it to be restful, mindful, rejuvenating, and spiritual, but sometimes I feel as though I have forgotten how to connect with it in that way, and I ask it to bend and contort to be what I want it to be.

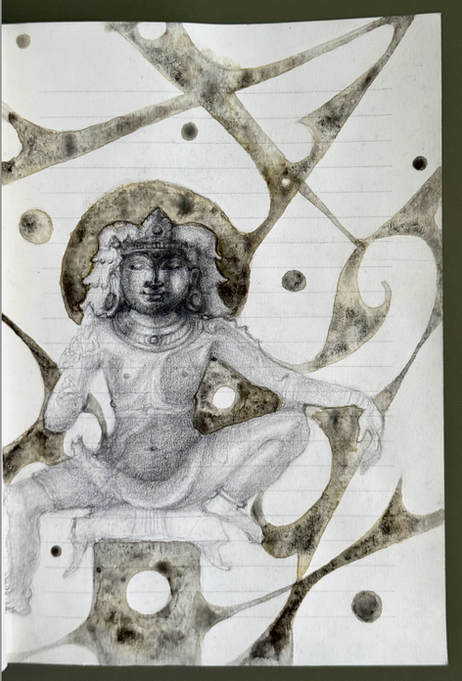

Anjanan Siva

Recessitation, 2025.

Graphite and Granulating Watercolour on Journal Paper.

I feel many artists may relate to the sentiment of having ideas that are so perfectly drawn out in their minds, almost becoming viscerally tangible, and yet, bringing them to life feels so arduous. I was not patient enough to complete rendering the body (based on a 12-13 C CE copper alloy Aiyanar statue at the V&A) and wanted to immediately jump into translating the background from my mind, which I wanted to create textural dialogue with. This piece falls somewhere between the curvilinearity of Neolithic Yangshao culture vases and the geometric works of contemporary artist Lukas Urban!

Biwei Liu

Unborn Zine, 2024.

Paper.

Unborn Zine is a collage composed of fragments from three perzines created during the early stages of a project that later became the installation WOMB. The original intention was to make a zine, it became paralyzed by its own evolving complexity, remaining instead as a fractured archive of prototypes within WOMB. It visualizes creative paralysis: the passion for the message lingers, but the "birth" has been deferred. It is a map of a creative process that continued to unfold yet forgot how to end.

Stacey Joseph

At the Threshold of Reflection, 2025.

Oil on 3/4" wood panel.

Unfinished piece meant to portray longing and/or stillness after loss. A feminine figure was meant to be leaning on the prominent tree, but fear of ruining the first layer (even though it felt unfinished), kept it from being worked on again.

Melanie Fujs

Labour Movement, 2024.

Cotton-linen blend canvas fabric, polyester, cotton, and wool thread, empty spools.

This piece is an exploration of the nature of labour and methodically persisting through a seemingly insurmountable task: hand sewing lines in an effort to fully encompass a large piece of fabric.

Stacey Joseph

Have You Found Your Way Home? 2024.

Oil on canvas.

Irene Blasig

Again, 2024.

Digital-Canon EOS R100 Camera. Triptych.

Perfection is sought but never attained, and eventually fatigue necessitates rest. Then the pursuit continues.

Sze Yin Shelby Wai

Columba livia, Lilium ‘Stargazer’, et Alstroemeria aurea, 2026.

Watercolour and water soluble colour pencils with pencil sketch.

My favourite things to draw have always been animals and organic forms rather than calculated, angular ones. Yet I somehow ended up in a highly logical science program. As a child, I carried my sketchbook everywhere; over time, daily sketching became weekly, then faded into textbook doodles. They say that to call yourself an artist, you must make art, but under an immeasurable workload, my passion survives quietly through aesthetically organized notes, daily makeup routines, and precise scientific illustrations. This work allows me to navigate my identity as both a science student and an art lover while keeping my creativity alive.

Ivy Thomas

Life Class, December, 2025.

Chalk on manila paper.

These drawings are messy, conflicting, and lack a sense of direction, similar to how my own creative passions often feel. I constantly find myself making excuses, perhaps out of fear, but in December I finally attended my first life class in 3 years. These drawings aren’t finished products; in fact, they were never intended to be seen. Rather, they are reminders of the artistic instincts that rest within me, my continuing desire to create, and visual proof that I am still capable of making art. They show me what can emerge when I don’t overthink what I create.

Luna Asuncion

Was I Something More? 2026.

Acrylic on canvas, Ribbon (White, Blue).

‘Was I Something More?’ is an acrylic painting that explores the jarring yet subtle loss of passions to time. The head of a horse sits plainly in the centre, yet its identity is complicated by an absence carved out of the canvas. This horn-like shape, lined with red, harkens back to its existence as a unicorn; a reference to childhood, magic, and flowing creativity. With it gone, is it simply a horse? Or does it continue to exist as a unicorn through the recognition of this absence?

Daisy Huang

i forgot how to decorate this thing, 2026.

Oil on canvas.

I forgot how to decorate this thing because I kept telling myself to press on. Immersed in my studies in chemical engineering, I find my hands have become wrinkled nitrile and confused when tasked to do something delightfully meaningless.

Selina Li

Yet to Bloom Again, 2026

Paper sculpture with watercolour. 10.5"x6"x3.5".

As inspiration withers, give grace in the frustration of seeking what was once a blooming bud of passion and fondness, longing for its blossom once more.

Amanda Veloso

You’ll Always Be an Art Kid, 2024.

Oil paint and mixed media on cotton canvas.

Built from memories of stickers, beads, rhinestones, doodles, and childhood play— I rediscover my identity as “the art kid” and the self I once created without hesitation. The feeling of freedom and creativity that comes with being an art kid never truly fades, it's become a fabric in my identity. Yet it also holds the tension between past freedom and present struggle; the gap between loving to create and struggling with how to begin. The materials become fragments of memory, tracing the fragile space between desire and paralysis; where creativity still exists, but reaching it no longer feels simple.

Call for Submission

The 2026 Winter Talking Walls exhibition, “sometimes i forget how to do things i say i like to do” invites visual artworks that explore what remains when passion comes to a halt; works that capture the fragile space between memory and oblivion, desire and doing.

This exhibition seeks to visualize creative paralysis: the moments when creative acts stop, but the passion remains.

We are especially interested in process-driven, experimental, and incomplete visual pieces; works that embody struggle, memory, and the tension between what was once effortless, and what now feels unreachable.

Eejin Choi and Mario Zhang

Hart House Art Committee

Student Projects Co-Chairs

Deadline: January 8th, 2026 11:59PM

Dive Into the Theme

Some day, you loved. And you begin to forget.

What lies between those two moments? “sometimes i forget how to do things i say i like to do” explores what remains when passion comes to a halt–the space that holds the tension and pain between memory and today, between desire and doing. In a culture that glamorizes speed and relentless productivity, this exhibition turns deliberately towards stillness, paralysis, and the gentle failure of intention.

We look closely at what happens in the in-between: what does it mean to love something yet lose the ability to practice it? When the mind remembers but the hands refuse? When you return to an act that once felt like home, only to find yourself a stranger there? When a gesture repeats without destination, the page remains stubbornly blank, and the act of putting even a single mark on the paper feels like lowering a massive glass sphere that might shatter at the slightest touch?

-

(Please note: This is a call for visual art, not for written pieces. The following artworks are examples of inspiration, not required references.)

“sometimes i forget how to do things i say i like to do” follows the framework of process art, which values the immaterial layer of ideas over material form. Where most artworks exist as a synthesis of form and content, conceptual/process art subordinates form entirely to meaning and artistic thought, bringing the process of creation to the forefront.

Eva Hesse, Untitled (Rope Piece), 1970. Latex, rope, string, and wire. © The Estate of Eva Hesse. Courtesy of Hauser & Wirth; photograph by Sheldan C. Collins

At the center is Eva Hesse’s work, Untitled (Rope Piece), 1970. This sculptural work was created by dipping two separate knotted rope into liquid latex, which then hardened the ropes, providing an underlying weblike structure for the sculpture’s gracefully arching loops and dense, twisted segments. Eva Hesse, in her process of conceptualizing this piece, noted; “hung irregularly tying knots as connections really letting it go as it will. Allowing it to determine more of the way it completes its self.”

We want to extend that philosophy into the psychological and emotional realm of creative paralysis. We are interested not only in depicting hesitation but embodying it–in works that carry the very texture of struggle, not as aesthetic choices but as lived experience. Consider this: what if the sketch you abandoned midway through is, perhaps, the most honest thing you’ve made?

On Kawara. I Got Up / I Met / I Went series, 1968-1979. Ink and stamps on postcards.

Take a look at the artwork I Got Up/ I Met / I Went series from 1968-1979 by On Kawara. The artist transforms routine into rituals. Each act of documentation–sending postcards stamped with the exact time he woke, mapping where he walked, recording whom he met. It suggests a compulsion to continue, even when meaning fades. It is in its repetition where both endurance and emptiness lie, reminding us of the echo of doing as a form of not-doing.

Lee Ufan, From Line, 1974. Oil on canvas. 71 ½ x 89 ⅜”.

Finally, Lee Ufan’s From Line (1974) distills the gesture to its vanishing point. Each brushstroke fades as the pigment runs out, tracing the breath between movement and stillness. The act of painting becomes an acknowledgement of its own exhaustion. It is, precisely, the act of letting the gesture stop.

Together, these works form the emotional architecture of the exhibition: the sagging rope, the mailed timestamp, the fading line–each a record of persistence within limitation. They are a reminder that failure to continue is not the end of a passion, but its most human moment.

------------------------------------------------

Who we invite

We invite those who can no longer easily call themselves “artists.” We often say, “I’m an artist,” or “I’m a writer.” but when the doing stops and only the identity remains, the fragile space between practice and self-reveals itself. Have you ever had questions like: how often must you paint to be an artist? Conversely, how long must you not paint before you lose the right to call yourself one?

Your eyes may still be fascinated by the composition, light and colour of some other artwork–but your hands no longer dare to translate what your eyes see. Have you ever felt ashamed, as though you were a fraud?

This exhibition is a space for that dissonance, for the failure of unrequited love. We aim to provide a space not for completions, but for those who once professed love to art and now wait for an answer that never returns, for artists who open a sketchbook only to close it again, for drawers filled not with finished works but with projects frozen mid-gesture.

This feels especially urgent now. Amid widespread burnout, instability, and the ceaseless demand for productivity, many of us are exhausted. And many of us are entangled in complicated relationships with the very work that was meant to sustain us. This exhibition is our response to the fact that difficulty matters; paralysis itself deserves to be seen.

---

What do you say?

Once, you loved something. And you are forgetting how to do it. If you once loved, what remains in your hands now?

This exhibition does not ask you to say, “that’s it, I’m done,” to whatever you loved (and certainly still love?). We neither glorify renunciation nor demand release. Instead, we wish to see how you live with your forgetfulness-those you have not yet finished mourning or cannot yet let go.

Really, what do you say? Do you say goodbye to past passions? Or do you still cry out for it to return? For some, this exhibition may be a farewell. For others, an act of resistance. It need not arrive at a conclusion, for that, too, is a path. To display what could never be finished does not mean to end it. Our aim is not to close, but the refusal of it. We are simply curious about how you continue to walk across all that you could not complete.

Like you, countless others walk past this hallway each day. What might these walls mean to you? We wish this wall to be a space where you, both as an artist and audience, can acknowledge and make visible the ongoing negotiation between who you were and who you are becoming, between the practice that once defined you and the silence that followed.

---

What we look for

We welcome works that locate hesitation, stagnation, and the fragile act of not-quite-doing. Unfinished projects, unresolved projects, sketches that circle without closure; process-based collages, annotated pages, diaristic fragments, notes to oneself spiraling into silence or repetition; repeated marks, gestures, or visual journals of ‘not-doing”--works that trace the days, weeks, or months of intention without execution, and works that metaphorically express fatigue, burnout, or creative exhaustion.

Let your submission be incomplete. Let it stutter, let it totter. Let it become the thing you made when you could not make.

Eejin Choi and Mario Zhang

Hart House Art Committee

Student Projects Co-Chairs

References

Hesse, Eva. 1970. Untitled (Rope Piece). Latex, rope, string, and wire. Whitney Museum of American Art. New York City, United States of America.

Kawara, On. 1968–1979. I Got Up / I Met / I Went Series. Ink and stamps on postcards. Museum of Modern Art. New York City, United States of America.

Lee, Ufan. 1974. From Line. Oil on canvas. Museum of Modern Art. New York City, United States of America.